Duterte’s China Pivot: What it Means for Indonesia’ Energy Industry

Author: Zev Faintuch

The winds in the Asia-Pacific are shifting eastward. Until recently, Indonesia and the other Pacific nations enjoyed security and economic growth under the umbrella of Pax Americana, a state of relative international peace achieved through the dominance of America and its allies. Yet now, American hegemony in the Pacific is all but a distant memory. China has emerged as The Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) largest trade partner and constitutes the top trading partner of every country in the region, including Indonesia. In light of the growing economic and military challenges posed by China, tensions in the East and South China seas have reached new heights. In order to placate the two rivals, in 2011, the Indonesian government embarked on a foreign policy of pursuing Dynamic Equilibrium: to act as a responsible middle power engaging in various regional multilateral institutions without taking sides on thorny issues. Despite Indonesia’s close security ties with the US, Jakarta will not enter into any formal alliance, as it prefers to play the two powers against each other.

Not only does Indonesia see itself as a neutral power, it is also possesses a wealth of natural resources. Moreover, its location gives it control over the some of the world’s most important shipping lanes. The Malacca Strait, a 500-mile long water corridor from the Andaman Sea of the Indian Ocean in the west to the South China Sea in the east, facilitates 30 percent of the world’s trade and accounts for 80 percent of the petroleum imported by China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Thus Indonesia’s geopolitical importance is equaled by its strategic control over the means by which Asia, the most energy-thirsty continent, imports its hydrocarbons. However, Indonesia’s role as a counterweight should not be taken for granted. Recent changes in the geological paradigm of the region may bring Indonesia into the Chinese sphere of influence, which in may turn adversely affect its blossoming energy industry.

Duterte’s Pivot

This month, Rodrigo Duterte, the outspoken President of the Philippines, cancelled joint naval drills with the US, signed thirteen bilateral agreements with China and declared a military and economic separation from the States. While it is difficult to draw conclusions from Duterte’s recent moves, his latest statements have set off alarm bells in Washington and many Asian capitals. But what does this mean for Indonesia?

The Philippines, once a stalwart ally of the US, is not the first Asian nation that has signaled a shift towards the People’s Republic. In a surprising move, on August 30, Vietnam’s Defence minister made a visit to Beijing were he laid wreaths on the Peoples Republic of China’s founding father, Mao Zedung – a clear signal of Beijing’s growing popularity in Hanoi. Vietnam is China’s most antagonistic maritime rival, sharing its maritime claims against China with the Philippines. If the two nations set aside their territorial disputes with China over the South China Sea, the US will have lost its military importance to the Southeast Asian states. In fact, as Zhang Baohui, a China expert explains: “…the US needs a narrative that paints China as an aggressor…the narrative needs a ‘victim’…” for the US to protect. If the two primary “victims” of the South China Sea dispute, Vietnam and the Philippines, pivot to China, other Pacific nations, like Indonesia, may follow suit. Many pundits fear that this recalibration of the geopolitical landscape may trigger “bandwagoning” behavior, thereby alienating the anti-China vanguard: Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

The Effects of a China-Pivot to Indonesia’s Trade Partners

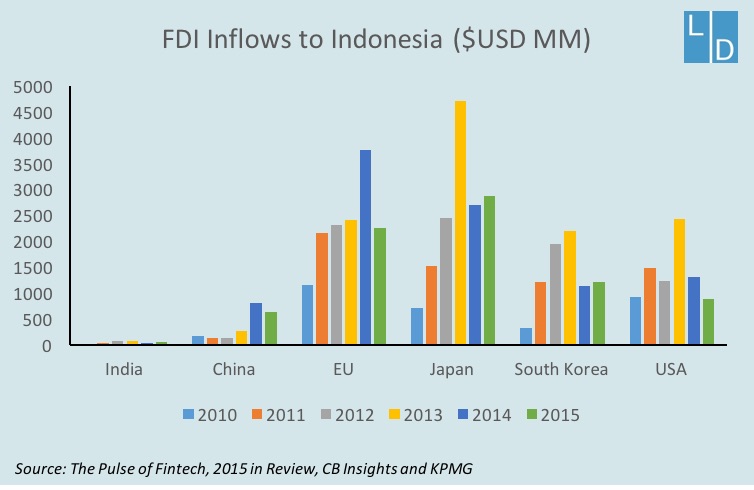

An Indonesian pivot to China could jeopardize its bilateral relationship with China’s main Asian rival: Japan. Japan is Indonesia’s largest creditor, export partner (see image) and investment benefactor. Currently, Kyoto injects $2 billion dollars per year of Foreign Direct Investment into the Indonesian economy which may even increase to $4 billion by the end of 2016. However, bilateral ties with Japan have become strained as of late. In September 2015, China beat out Japan’s bid to build a high-speed rail line in Indonesia. As a result, relations between the two nations began to decline. In March 2016, Jakarta scuttled Japanese energy giant, INPEX, and Royal Dutch Shell’s joint venture to develop one of Asia’s largest off-shore gas fields in favour of building an onshore facility instead, thereby, putting the companies at risk of losing their capital spent on exploration. Moreover, to the dismay of Tokyo, Indonesian President Jokowi has visited Beijing more than any other major capital in the region. In fact, since reaching office in 2014, Jokowi has visited China five times. Closer ties to China, paired with further moves to alienate Japan and its business interests could mean disaster for Indonesia’s energy industry.

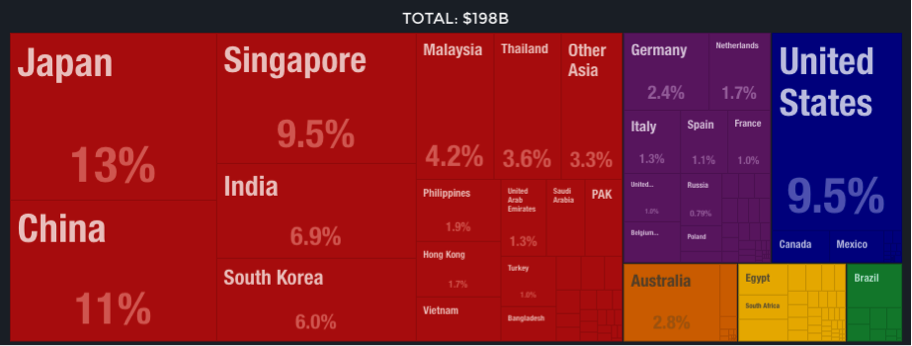

Indonesia’s Export Partners by Volume of Trade

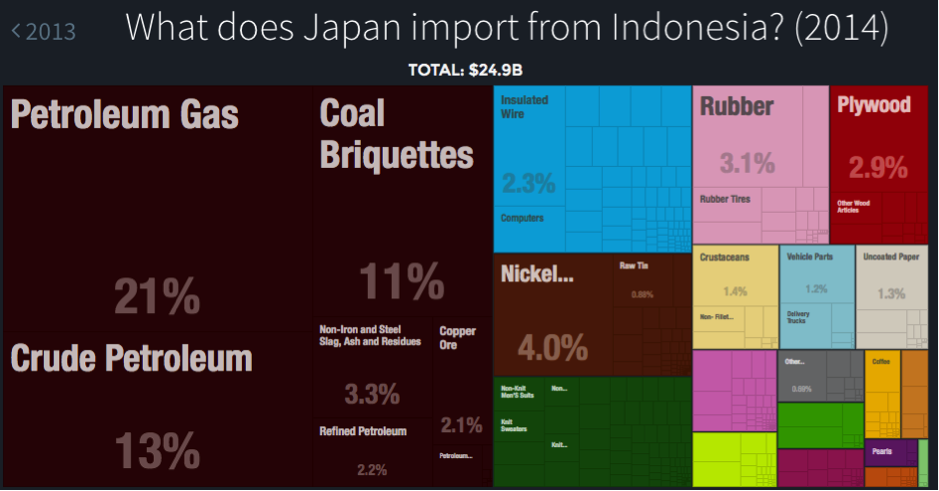

Japan is one of Indonesia’s largest importers of energy (see image below). More importantly, Japan has the technological know-how to create the much needed infrastructure Indonesia requires to expand its energy industry. If Indonesia follows the Philippines into the Chinese camp, it would be difficult for the nationalistic Japanese government to justify its foreign aid to and its lending and imports from Indonesia to its vehemently anti-China voter base. An Indonesian pivot to China would adversely impact its energy sector and economy as a whole.

In addition, an Indonesian pivot to China would also complicate its bilateral ties with the US. American oil companies produce over 50 percent of Indonesia’s crude oil necessary for both its domestic needs and foreign exports. The current election cycle has brought a renewed focus on China. It is possible that that American lawmakers and or the incoming administration may seek to curtail the interests of US-owned companies in Indonesia, spelling catastrophe for Indonesia’s energy industry.

Only time will tell whether or not Indonesia will fall into China’s sphere of influence, thereby alienating both Japan and the US. Since Indonesia is a democracy, the regime’s legitimacy is predicated on the collective will of the people. Indonesian society is generally anti-Chinese. The Indonesian media has been critical of Chinese foreign workers. Furthermore, it is difficult to fathom that Indonesia’s security establishment would allow the civilian government to tarnish its ties to the Japanese and American militaries. While it is possible that Duterte’s abandonment of Washington may cause a pro-China ripple effect in Asia, it is likely that Indonesia will continue promoting Dynamic Equilibrium while maintaining its current geopolitical position.