Environmental Regulations and Sustainability

Primary Analyst: Kamalaya (Kyla) Yang

Team Leader: Julie Flesch

The past two decades have seen a surge in global demand for soy and meat products, leading to the rapid expansion of agricultural production in South America. As the world’s fourth largest exporter of soybeans and one of the top ten cattle producers worldwide, Paraguay has become a target of mounting pressure to implement stronger environmental regulations around the globe. Previously home to the second-highest deforestation rate in the world, nearly 7 million hectares of Paraguay’s Atlantic Forest were lost to slash-and-burn methods of agriculture and ranching. Growing public concern for the environment has generated demand for stronger regulation to protect remaining forests and limit pesticide-use and land disputes between large corporations and local populations. Both the prospect of increased regulations directed at promoting sustainability and reducing emissions and the social conflict generated by large-scale agricultural activities pose risks to investors in the agricultural sector.

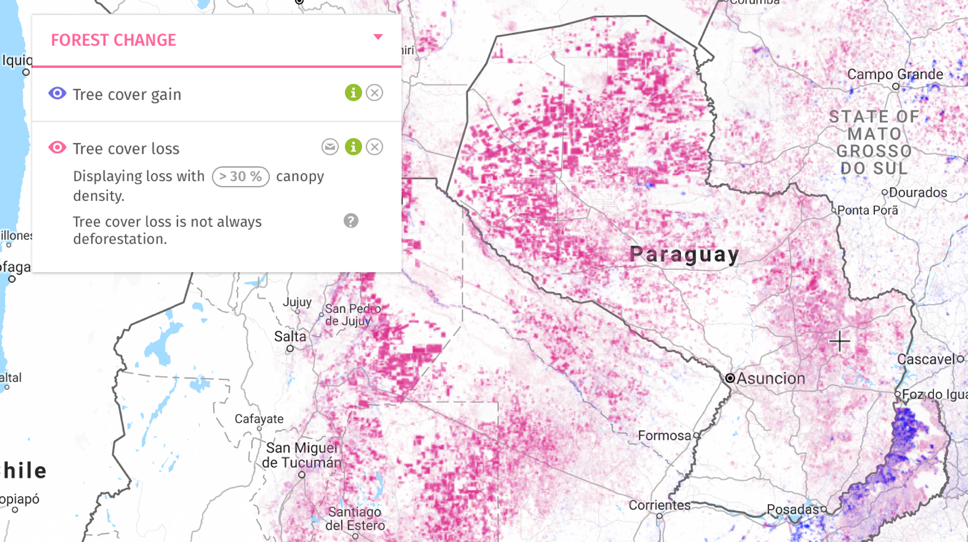

Total tree cover change in Paraguay from 2001-2016 includes a 5,099,895 Ha loss and a 51,023 Ha gain. Source: GlobalForestWatch.org

Sustainability

In 2004, Paraguay instituted a “zero deforestation” law for its Atlantic forest. This particular biome continues to be the most highly regulated within the country, with 100% of its forest protected. Paraguay’s six remaining six biomes fall within the Chaco region that spans across Paraguay, Argentina and Bolivia. The Chaco forest is Latin America’s second most important forest, behind only the Amazon in terms of size and biodiversity.

Compared to Paraguay’s Atlantic region, the Chaco is far less regulated and has just over half of its forests protected. The “environmental management plan” for Chaco, developed from 2007-2008, is not legally binding and only contains recommendations. As well, stringent regulation to the level of that of the Atlantic forest is unlikely to develop in the future: a “zero-deforestation law” was proposed for Chaco in 2009, five years after such a law was established in the Atlantic forest, and it was rejected.

Despite the introduction in 2010 of an almost real-time body of data to monitor deforestation in the Atlantic region, the country still has “notably low enforcement of public regulations, with very low fines, low field-enforcement capacity, and very high levels of corruption.” While 100% of the Atlantic Forest is protected, in reality only 50% of the forest is effectively enforced by law. These figures are even lower in the Chaco region, where only 25% of the forests are effectively enforced compared to the 50% protections outlined by regulations. While deforestation is closely monitored in both regions, actual enforcement capacity is significantly lacking.

On the whole, the risk of deforestation regulation to agro-business lies primarily in its potential to reduce profit margins. The reduction in available supply of land caused by the creation of legally protected forest reserves – given that demand remains more or less constant – has the potential to increase land prices and, therefore, reduce the profit margin of agricultural companies. The sanctions for non-compliance, given the low risk of being caught and the low fines if one is caught, pose a comparatively smaller risk. In any case, due to the inconsistent nature of deforestation regulation across the country, moving operations to ‘deforestation havens’, such as within the Chaco biome, would mitigate some of the transaction and opportunity costs associated with operating in a more regulated area.

Further, a number of certification programs such as the The Roundtable for Responsible Soy (RTRS) have emerged to promote the adoption of sustainable best practices and to increase transparency within supply chains. In practice, this voluntary program has been highly ineffective, doing little to achieve any social or environmental goals while the use of pesticides and rampant deforestation continue unabated. While the RTRS program may do little to tackle environmental challenges, it may prove to be an effective program for rubber stamping agro-products should demand for sustainability grow among Paraguay’s main trading partners. For example, the European Commission accredited the RTRS in 2011 to approve certified soy for use in the EU biofuel market. Greenwashing programs may prove to be an effective risk mitigation strategy for corporations looking to either create a smokescreen around their environmental practices or to take advantage of opportunities offered by premium markets where consumers are particularly sensitive to their carbon footprint.

Social Conflict

This increased global demand for agro-products has greatly affected the livelihoods of Paraguayan farmers. In the last decade alone, factory farming has advanced across the country's most fertile areas turning 2.5 million acres into soybean fields, displacing large numbers of subsistence farmers and small-scale cattle barons. Due to the lack of environmental and land use regulations, the MNCs operating in Paraguay are especially mobile. Once they lay waste to one piece of land, they can easily move operations elsewhere, disrupting and endangering a new local population. In response to this activity, the campesino peasant farmers have emerged as an organized interest resisting the encroachment of agro-giants and demanding strong environmental reforms.

The farming practices of large multinational corporations have had devastating health effects for populations living nearby. Soy farming in particular dumps over 24 million litres of toxic agro-chemicals in the country per year. An investigation has revealed that in several areas of high soy production 78% of families experienced health issues caused by pesticides used to spray crops, despite laws regulating spraying practices.

This health crisis, combined with the massive debts local farmers have incurred as a result of climate change and lost crops, have encouraged the radicalization of the campesinos. In a series of recent protests, these small-scale farmers have demanded that the government declare a state of emergency, forgive the debts of small-scale farmers, invoke greater environmental regulations, and provide credits to stimulate the local agricultural industries. Apart from the general instability generated by these riots, the campesino uprising poses a risk to investors in the industry should the protests be successful in pressuring the government to implement stronger regulations. If the government does begin to strengthen pesticide regulations, mandate land usage and intervene in conflicts over land, operating costs will rise, the mobility of MNCs will be restricted and it could become much more difficult for corporations to wrest land from local populations.